Grades Can Hinder Learning. What Should Professors Use Instead?

By Beckie Supiano

July 19, 2019

Notre Dame, Ind.

Susan D. Blum has been teaching college students for 30 years. For much of that time, she was a conventional grader. But finals week at the University of Notre Dame this past spring found Blum, a professor of anthropology, wrapping up her courses in an unconventional way. Instead of giving an exam, she held short one-on-one meetings with each of her students to discuss what they had learned.

The conversations built on a concluding reflection Blum had asked students to spend two or three hours writing, answering questions like: “Did you learn something you hadn’t expected to learn?” and “What work of yours was especially strong? Why? Explain its positive features.”

During one meeting, Mia DiCara, a student in her “Food and Culture” course, said she’d been mulling a comment Blum made on her first assignment, that it “was good, but nothing earth-shattering.”

“Did I say that?” Blum asked.

“Yeah, you did,” DiCara said, laughing. “But I thought it was great because I was like: Yeah, you’re right.”

DiCara pushed herself to be more creative as the course went on. Her work, she said, got stronger as a result.

That is the kind of growth Blum wants students to experience in her courses. But her research and personal experience have persuaded her that it’s difficult to achieve when students are graded. Blum has come to the conclusion that grades are meaningless, even harmful. Grades, Blum is now convinced, are a barrier: between students and professors, between students and learning.

So Blum has stopped grading. She has joined the ranks of college professors and schoolteachers experimenting with “ungrading,” a set of practices meant to redirect time and attention to more important things. Like most professors, Blum can’t discard grades completely — she still has to hand them in at the end of the term. But that leaves the rest of the semester to help students question the premise of those grades and encourage them to focus instead on their learning.

Near the end of her chat with DiCara, Blum asked a question: “What grade would you give yourself?”

“For the amount of effort and participation that I had in the class,” DiCara said, “I think it’d be an A.”

DiCara was expecting the question but still felt “weird” answering it, she said later. She knew that in most cases Blum gives students the grade they suggest.

This is not how college usually works.

A Different Approach

In place of a final exam, Susan Blum asked students in her Food and Culture course to write responses to these questions before meeting with them in individual conferences.

Grades are among education’s most recognizable symbols, up there with chalkboards and graduation gowns. Plenty of instructors use them for years without ever wondering why.

But let’s take a moment and ask. Why grade? To give students feedback, a professor might say. To measure learning. To motivate.

Here’s the problem: Decades of research undercuts these assumptions.

Take the issue of feedback. It comes in two main forms: evaluative feedback, like letter grades, and descriptive feedback, like the comments a professor might leave on a paper. In either case, feedback is meant to help students improve. Does it?

A set of influential studies of schoolchildren conducted in the 1980s by Ruth Butler, a professor of education at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, suggests that the two types of feedback affect students in very different ways.

In one study, Butler and a colleague tested the effect of three forms of feedback on students’ subsequent performance and motivation: a grade, comments (noting an aspect of the task performed competently and one that could be improved), and nothing. Students who received either grades or comments performed better on a later quantitative task than the students who did not get any feedback.

But only those who received comments did better on a subsequent qualitative task, which required creativity or problem-solving. The findings also indicated that comments supported intrinsic motivation, while grades weakened it.

The implication? Grades, the researchers wrote, “may encourage an emphasis on quantitative aspects of learning, depress creativity, foster fear of failure, and undermine interest.”

But what happens when professors give a grade and write comments, too? That combination must be better, right? Butler addressed that question in a second study, where one group of students got a grade, one got comments, and one got both. The effects of a grade and comment together, she found, were similar to those of a grade alone. Instructors, in other words, can’t shield students from the effects of grades by including comments.

Butler also tested which form of feedback students remembered later that same day. Nearly all the students who received both a grade and comments remembered the grade. Fewer than half remembered any part of the comments.

That’s just one example of research that challenges the effectiveness of grades. Other studies have found that they reduce students’ interest in what they’re learning. They make students more risk-averse, less curious, and more prone to focus on their performance instead of the task at hand. Grades tempt students to cut corners, including by cheating. They position students and professors as adversaries. They make it harder for students to think for themselves.

Much of this literature was collected by Alfie Kohn, author of more than a dozen books on education and human behavior, in Punished by Rewards: The Trouble with Gold Stars, Incentive Plans, A’s, Praise, and Other Bribes (Houghton Mifflin, 1993) — a book that has served as a touchstone for Blum. Although it was published more than 25 years ago, its message remains iconoclastic.

As his title suggests, Kohn’s main critique has to do with motivation. He assumes his readers already understand that punishing people — whether students, employees, or one’s children — is ineffective. His aim is to convince them that rewards are the other side of the same coin.

Rewards, Kohn argues, serve the same function as punishments: They allow those with more power to exert control over those with less. And people — who have a strong drive toward autonomy — tend to resist being controlled.

Grades do have a purpose, Kohn writes: They sort students. There could be situations, he writes, in which this sorting is useful, such as determining student placement. But teasing out the differences between a B- and C+ essay — or worse, failing students who did just a bit worse than their peers on a test because a grading curve demands it — orients professors toward a very different goal than helping every student learn.

It can be hard, though, to criticize a system that rates you, personally, as a big success. That’s true for students at selective colleges. And it’s especially true for their professors, who have been in the system longer — and have made it to the top.

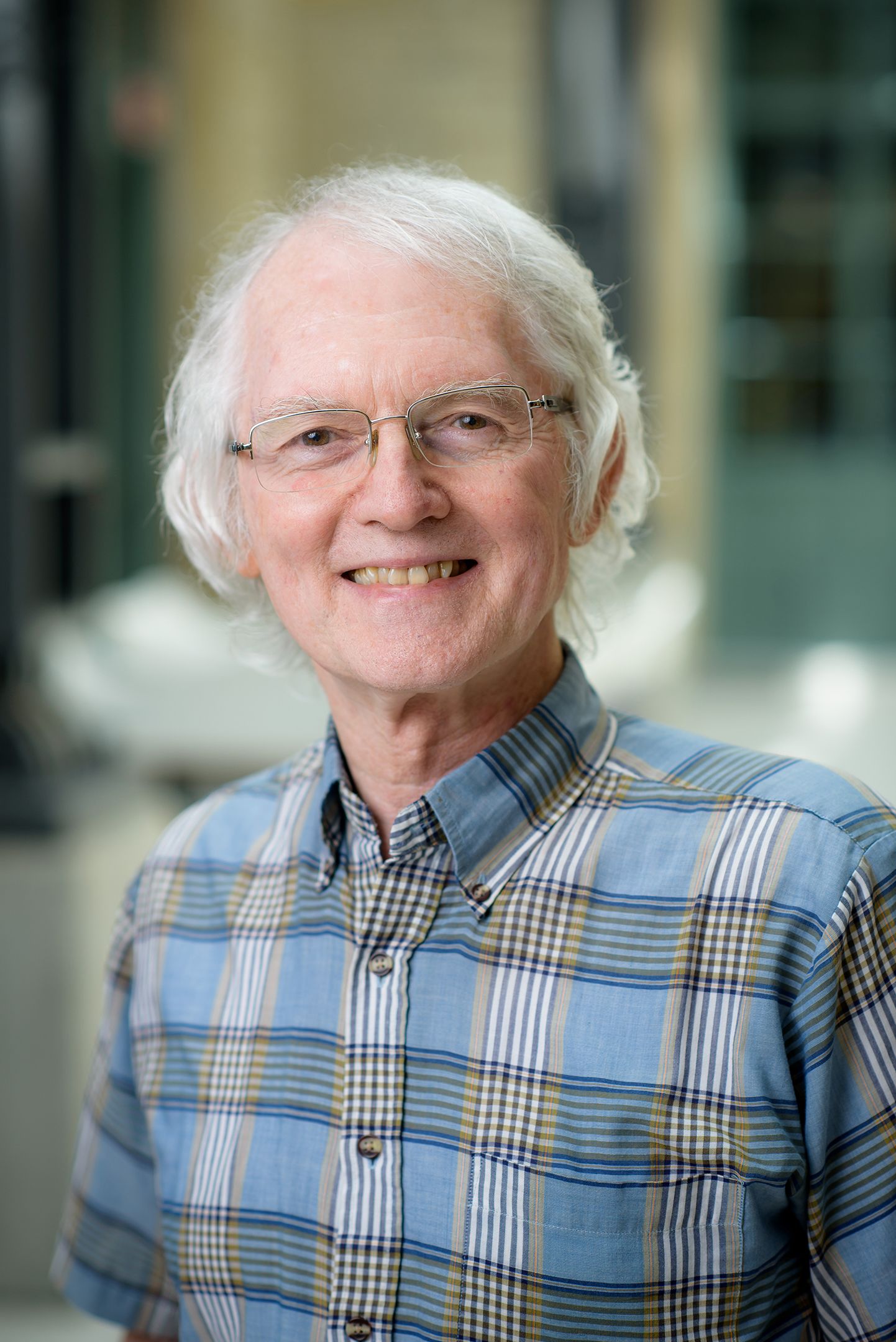

Susan Blum, an anthropology professor at the U. of Notre Dame, came gradually to the “ungrading” philosophy. She described that progression in her 2016 book I Love Learning; I Hate School: “For decades the focus on grades seemed to me, as a teacher, natural and right. Then it became irritating. And finally it signaled a grave mistake.” (Stephen Hill for The Chronicle)

Susan Blum, an anthropology professor at the U. of Notre Dame, came gradually to the “ungrading” philosophy. She described that progression in her 2016 book I Love Learning; I Hate School: “For decades the focus on grades seemed to me, as a teacher, natural and right. Then it became irritating. And finally it signaled a grave mistake.” (Stephen Hill for The Chronicle)

Before she became a professor, Blum was an excellent student. She was, and remains, a rule follower. A voracious reader and prolific writer — every year she drafts a novel for fun — Blum is the kind of professor who assigns scads of reading and really wants students to do it.

Blum is not, in other words, the kind of overly relaxed professor you might imagine when you hear that someone doesn’t give grades. She is, rather, a scholar who experienced a slow and sometimes painful epiphany.

Reading books like Kohn’s and the research underlying it was just part of what changed her mind.

Her personal life played a role. While Blum, her husband — also a professor — and her older daughter were all studious and rule-abiding, her younger daughter was a very bright pusher of boundaries. She went to Hampshire College, which does not give traditional grades.

Another strong influence on Blum was her disciplinary lens. She is trained in part as a psychological anthropologist, meaning she takes a cross-cultural approach to psychological questions. Blum became interested in what her field has to say about childhood, a topic she sometimes teaches. She came to believe that in the United States, school “infantilizes” students by having them depend upon teachers’ assessment of their work.

But perhaps the biggest factor in Blum’s departure from grades was the arc of her own scholarship: The stages of her evolution can be marked by several of the books she has written. It began more than a decade ago with a book on China, where she has conducted much of her fieldwork.

In Lies that Bind: Chinese Truth, Other Truths (Rowman & Littlefield, 2007), she contrasts American and Chinese cultural norms on the permissibility of dishonesty in public interactions.

That book led her to investigate a form of deception that’s a major worry in her line of work. She wrote My Word! Plagiarism and College Culture (Cornell University Press, 2009), which rejects traditional explanations for students’ cheating. Blum argues instead that there’s a “mismatch” between the expectations of students and colleges, in part because of a cultural shift. Many younger people, she writes, emphasize outward behavior — which might vary by context — over authenticity, and collaboration over originality. From this perspective, academic concerns about authorship are simply not a meaningful priority.

Another factor: Students’ goals in college are often more utilitarian than their professor would wish. Blum would never condone cheating. But if students have little interest in the work they are supposed to do, and see it only as a means to an end, she says, plagiarism is then rational.

Ever since, Blum has continued to pull on the thread of American higher education in her research. And that work changed her view of students. Earlier in her career, Blum was frustrated by what she saw as students’ lack of interest and sense of entitlement. Over time, she changed her mind. The problem wasn’t students. It was their schooling.

By the time Blum wrote I Love Learning; I Hate School: An Anthropology of College (Cornell University Press, 2016), she was very uncomfortable with grades. Early in the book, she traced her own progression: “For decades the focus on grades seemed to me, as a teacher, natural and right. Then it became irritating. And finally it signaled a grave mistake.”

Later on, she sketched an early version of her ungrading approach, in which students filled out a self-evaluation of their own assignments, describing, among other things, their strengths and weaknesses.

“If I could make only one change to conventional schooling,” Blum wrote, “it would be to stop giving grades.”

But she couldn’t quite figure out how to do so in her own courses.

Not long after the book came out, that tension brought Blum to the point of despair. “Do I have to quit?” she wondered.

A tenured full professor at a prestigious university at this point, Blum was serious enough in her unease to respond to headhunters about administrative jobs, and even took some interviews. But staying in higher education in any capacity felt indefensible.

What saved Blum was, characteristically, a book: Hacking Assessment: 10 Ways to Go Gradeless in a Traditional Grades School (Times 10 Publications, 2015), by Starr Sackstein, then a teacher at a public high school in New York.

In that environment, Sackstein was very much expected to hand in grades. But she figured out a way to push them the margins, focusing instead on what students knew and could do.

“The key insight for me,” Blum says, “was that you could have a system that you believed in, in a structure that was still conventional. So I didn’t have to quit, I didn’t have to go to Hampshire College. I could stay in my job and just align my practices with what I knew to be better educational practices.”

In the fall of 2016, Blum went to tell her department chair, Agustín Fuentes, that she wasn’t going to grade anymore. She would hand in final grades, but they would usually be whatever students awarded themselves.

Instead of grading students, Blum would ask them to reflect extensively on their own work, writing a self-assessment for each assignment, and longer ones at the middle and end of the course. She would provide feedback and meet individually with each student.

Fuentes wasn’t especially surprised. He and Blum had discussed her perspective on grades over the years, and he agreed with parts of it.

They discussed her plans. Fuentes remembers pushing her on a few points, and ultimately feeling satisfied. Still, he says, what Blum is doing requires “a kind of fearlessness.”

Nonetheless, Blum always feels a little nervous when it’s time to tell new students her position on grades.

She no longer mentions grades on her syllabus. And she doesn’t talk about them on the first day of class, either — she wants students to get a feel for the course first. “By the time I tell them that we’re not really grading,” Blum says, “I hope they’ve learned something, they’ve enjoyed learning it, they felt comfortable learning it. And then I just sort of make it explicit what we’ve been doing implicitly anyways, which is focusing on the learning.”

To many students, getting good grades is a central goal in college, so taking them off the table is disorienting. Some students, Blum says, feel anxious without a regular sense of how well they’re doing. After all, they’ve been conditioned by years of traditional education.

That’s true of students in general. And it may be especially true at Notre Dame, where 38 percent of freshmen ranked in the top 1 percent of their high-school class. For many, concerns about grades don’t end with undergraduate admission, either. Twenty-two percent of Notre Dame’s graduates go straight on to graduate school, and medical school is a common destination.

Blum hopes they’ll at least question that status quo. She describes how her thinking about grades has changed over time. She shares what the research on grading shows. Sometimes, there are students who’ve taken a course with her before and can vouch for the process. That always helps.

Without grades, Blum tells them, students can learn what they want to, the way they want to. They can be creative and take risks.

Ungrading: 4 Approaches

Jesse Stommel

Executive director of the Division of Teaching and Learning Technologies at the University of Mary Washington

Stommel has students write several self-reflections, with varying levels of guidance, during the term. Because he is required to hand in final grades, Stommel has students determine their own. He reserves the right to change them. In the rare cases when that happens, he’s more likely to raise a grade than to lower it.

Starr Sackstein

Consultant and former

high-school English teacher

Sackstein collaborated with her students to design curriculum and standards. She gave them lots of feedback, in writing, in person, and using technology. At the end of the marking period, she met with students to discuss their work and decide together on their grade.

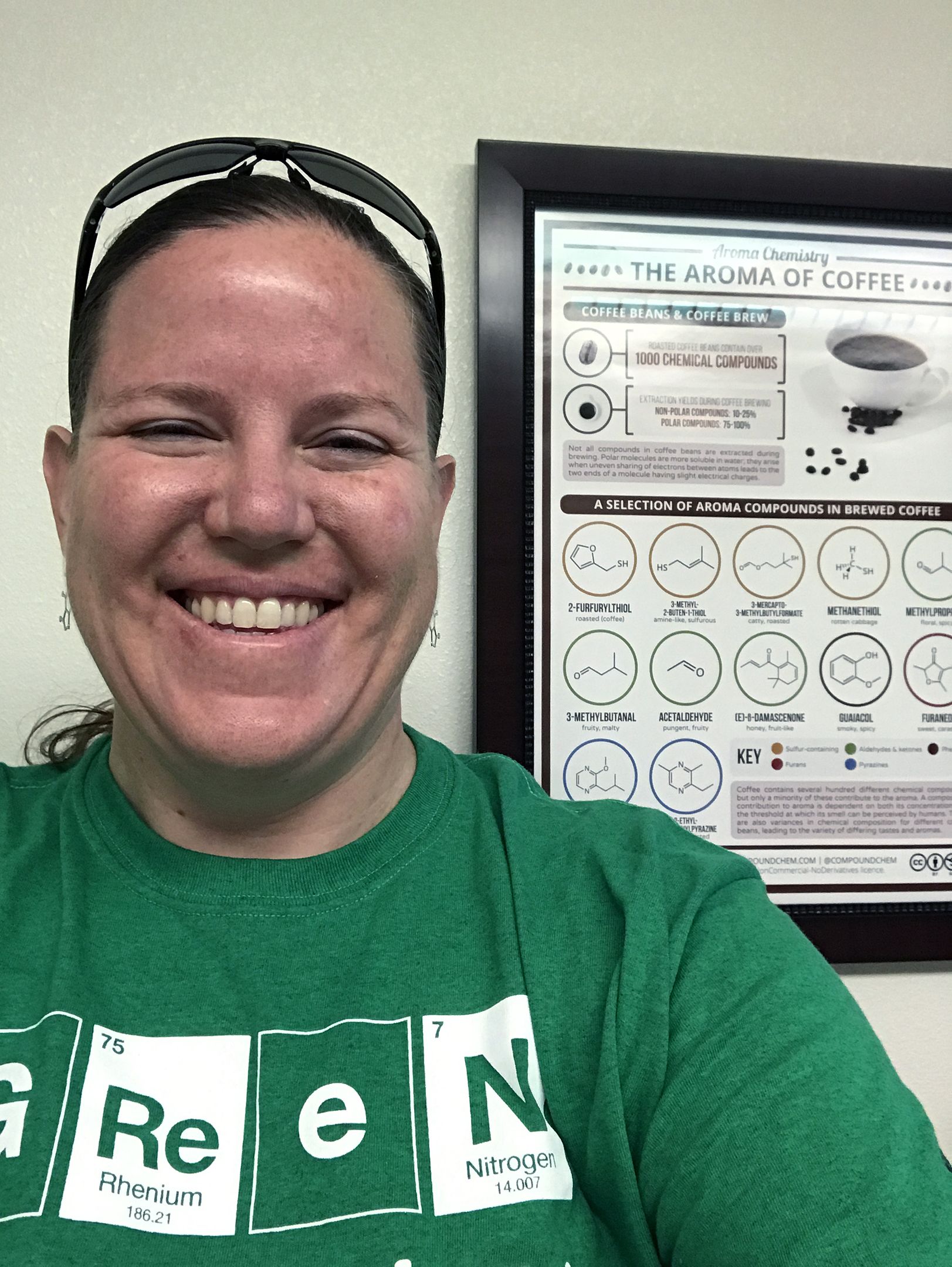

Clarissa Sorensen-Unruh

Full-time faculty member teaching chemistry at Central New Mexico Community College

A newcomer to ungrading, Sorensen-Unruh focused her effort on the three midterm exams she gave in her “Organic Chemistry II” course. She gave students feedback but kept the point totals she would assign to herself and asked students to grade their own exams. In most cases, Sorensen-Unruh averaged the number of points she gave students on each problem with the number they gave themselves.

Christopher K. Riesbeck

Associate professor of computer science at Northwestern University

Riesbeck’s students can choose from a set of exercises to work on. Once they have working code for an exercise, they submit it to Riesbeck, who critiques their work and returns it for revision. The cycle continues until Riesbeck has nothing left to critique. At the end of the term, he assigns grades based on progress, quality, and effort.

Jesse Stommel

Jesse Stommel

Starr Sackstein

Starr Sackstein

Clarissa Sorensen-Unruh

Clarissa Sorensen-Unruh

Christopher K. Riesbeck

Christopher K. Riesbeck

Ungrading is not an end in itself. It’s meant to support a vision of learning as something powerful, personal, and never quite finished.

To Blum, ungrading is in keeping with a number of changes she’s made in her classroom over the years. She now asks students to call her by her first name. She has moved away from setting and enforcing policies. Her syllabi have gotten shorter. If she notices a habit — attendance-taking, for example — that feels at odds with her focus on helping students learn, then she tries to break it. More and more, students take the lead in her courses.

The same emphasis on students’ owning their learning runs through a book Blum is editing, “Ungrading: Rewarded by Learning.” It contains chapters contributed by professors and schoolteachers who take different approaches to ungrading, Sackstein among them. Kohn is writing the foreword.

Growing numbers of professors are curious about ungrading, says Jesse Stommel, a contributor to the book. Stommel, executive director of the Division of Teaching and Learning Technologies at the University of Mary Washington, has taught without traditional grades for 20 years. Early on, the practice was “relatively fringe,” he says. But colleges’ efforts to measure learning, he says, have led more professors to seek alternatives.

Sometimes, Stommel hears from instructors who are intrigued by ungrading but don’t know where to start. His advice: Talk with your students about grades. “There’s a way in which just demystifying grades for students and sort of giving students a sense of agency within the system they’re working inside is an amazing first step.” Even if students encounter just one professor who does that, Stommel says, it can challenge their assumptions.

While Stommel champions ungrading, he also says it must be done with care. Professors must guard against inadvertently holding students to unspoken standards. That, he says, is particularly harmful for disadvantaged students who come to college less familiar with the “hidden curriculum” that orients insiders.

Guarding against that, Stommel says, requires “thinking about how it works, thinking about why you’re doing it, thinking about how it’s affecting your students, and getting to know your students on a personal level.” In short, he says, “keep one eyebrow raised, even in ungrading.”

Professors are known for their skepticism, and Blum organized her book with this audience in mind. She felt especially strongly about including the experiences of professors in STEM, whose chapters, she hopes, will make it harder to dismiss ungrading as some wishy-washy humanities thing.

When people first learn about ungrading, they can usually imagine how it would work in a literature course. The difference between a B paper and a B+ one is often seen as subjective. But ungrading’s application to STEM may be less obvious. In these disciplines, students either have the right answer or they don’t.

Sure, problems in STEM often have one correct answer, says Christopher K. Riesbeck, one of the chapter authors. What really matters, though, is how students arrive at it.

Riesbeck, an associate professor of computer science at Northwestern University, has long taught using a critique-based system in which students submit code, receive feedback, and refine their work over and over until he runs out of critiques. Here’s the thing: Riesbeck doesn’t critique students’ assignments until they’ve come up with working code that passes several checks. The entire process is about improving something that already works. It’s about mastery.

Like Blum, Riesbeck awards grades only at the end of the semester, when he’s required to. But he doesn’t usually use the word “ungrading” to describe his process. When people hear the term, they often get hung up on the idea that grades are absent. The point, he says, is that they’re not needed.

Students might not need grades as motivation to learn. But grades are still the currency of the education system. That’s something that weighed on Clarissa Sorensen-Unruh, a newcomer to ungrading, when she designed her approach. She blogged throughout her semester of ungrading and is also writing a book chapter.

Sorensen-Unruh, a full-time faculty member teaching chemistry at Central New Mexico Community College, knows that for many students, her Organic Chemistry II course is a required step in a larger undertaking: transferring to a four-year institution. Many of them are fulfilling a requirement for professional school in the health sciences. She simply couldn’t risk raising questions about her students’ credentials.

To address this concern, Sorensen-Unruh graded the final exam in a traditional manner while experimenting with the course’s three midterm exams.

When reviewing the midterms, she left comments, but indicated points only in her grade book, not on the tests themselves. When students got their tests back, they looked at their own work and the professor’s remarks and suggested their own point total. In most cases, Sorensen-Unruh averaged the scores students gave themselves on each question with the one she had given them. To avoid students’ inflating their scores, she awarded bonus points if their overall score was within one standard deviation of hers.

And what if every student inflated his or her grade? That’s one of the first questions many professors ask about ungrading, especially the forms in which students assign their own grades.

That worry, of course, is part of broader concerns that too many students are getting high marks. In the real world, critics maintain, not everyone can get an A.

Actually, in the real world, there are no A’s.

Back before she figured out how to push them to the edge of her courses, that’s something else that bothered Blum about grades: They’re artificial. “Yes, in jobs and in life some people are more successful than others;” she wrote in I Love Learning, “but how would we compare a salesman and a carpenter? There is no single scale.”

When their formal education is over, students will have to come up with some other way to think about their performance, their progress, and what success looks like in their work and lives. Ungrading can give them an early start.

Beckie Supiano writes about teaching, learning, and the human interactions that shape them. Follow her on Twitter @becksup, or drop her a line at beckie.supiano@chronicle.com.